Source: The Transport Politic

In early 2010, the U.S. DOT announced that it would award a $25 million TIGER grant to Detroit to begin construction on a new light rail line along that city’s central spine. For two years, hope spread through America’s most notorious shrinking city: This project, perhaps, would provide the boost to resurrect the Motor City.

Last week, just as the latest TIGER grants were being unveiled for other cities, local leaders announced they would reneg on that promise due to a fear that operations costs would be impossible to cover. A less aesthetically pleasing — but far more extensive and regionally funded — BRT program would be inserted in its place.

This situation speaks two realities: First, Detroit continues to be a mess — both politically and financially. Leaders of surrounding counties have shown themselves unwilling to compromise, expressing hostility over the idea that local tax funds might go to aid the transportation system adjacent city rapidly descending into zombie mode. Second, the U.S. DOT rushed its initial selection of TIGER grant recipients and showed that it was incapable of following through. Detroit’s fiscal situation in 2010 was not much better than it is today; how could the government have expected the city to fund the project’s operating costs then if it can’t now?

For Detroit’s civic ambitions, the death of the $528 million light rail plan is devastating news. Over the past two years, as it has become increasingly apparent that the current situation is far from sustainable, business, political, and community leaders have staked their hopes for the future of the city on the rail project. Not only would the 9.3-mile transit line running up Woodward Avenue provide substantially improved access to downtown, they argued, but it would spur a major increase in development in the area. Mayor Dave Bing suggested that the population of the city would be encouraged to relocate to more transit-accessible neighborhoods, especially along the corridor. The light rail line would give the city a competitive advantage.

This outlook was never realistic: No rail project, no matter how nice, can singlehandedly reverse the systematic decline of a once-huge city. Development will come to downtown Detroit when there is a demand for housing units and employment there, not when there are tracks along Woodward Avenue. Moreover, the city’s existing employment-housing imbalance, in which 60% of the city’s job holders go to the suburbs for work, means that a downtown-focused project would likely be ineffective in resolving the commuting needs of many people.

The decision to cancel the project, however, came down to the fact that Washington was worried that the City of Detroit would be unable to subsidize the costs of operation. The city’s existing transit services are in turmoil: The downtown People Mover, a one-way automated elevated loop line, practically shut down this month due to a lack of agreement about funding it. Fewer than half of the city’s buses are in operation, due to neglect and maintenance issues. Suburban bus services, offered by SMART, have declined considerably faced with less-than-expected revenues. To make matters worse, there is little fare or service integration between the three operations.

The Federal Transit Administration expressed concern that the situation could get even worse if the light rail line’s operations costs required the elimination of some bus services. Several months ago, FTA head Peter Rogoff argued that Detroit’s goal to use annual state and federal grants as the primary source of funding was an untenable long-term approach.

But an alternative providing a steady revenue source would require regional cooperation, and indeed the government hoped that the Detroit region would integrate its transit offerings into a single regional authority. Yet disagreements across county lines have imperiled the concept of a regional transit authority repeatedly; a $600 million effort to build a regional rail system in the 1970s, for instance, was scuttled when surrounding counties refused to join in. Oakland County Executive L. Brooks Patterson argued against a regional transit tax this summer and in fact has been a stated proponent of, as he says it, sprawl.

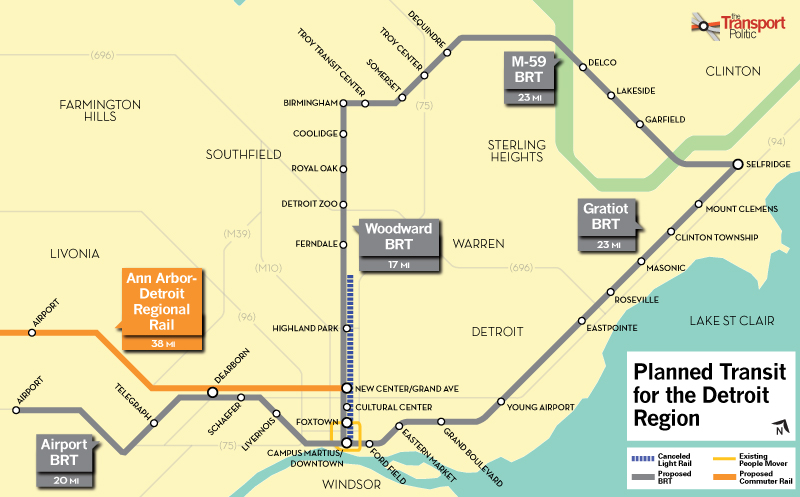

The new bus plans, serving surrounding Macomb and Oakland Counties as well as Detroit’s Wayne County, apparently will relieve that tension because, unlike the light rail efforts, they would not be focused on the central city’s downtown. The regional transit authority is again being promoted, this time by Michigan Governor Rick Snyder.

Four BRT corridors would run 83 miles between the region’s largest destinations. 34 stations would connect downtown with the airport, Birmingham, Troy, and Selfridge, primarily along Woodward Avenue, Gratiot Avenue, Michigan Avenue, and M-59. The extensiveness of the network as proposed will provide a level of service an order of magnitude more significant than would have the light rail.

The project is in the earliest stages of planning, so the levels of service to be offered by this BRT network are unclear. How many exclusive lanes will be provided for the buses, for example?

This proposal is similar to the 67-mile “Golden Triangle” announced by suburban leaders in Spring 2010. Yet while that less-lengthy plan would have cost about $800 million, Governor Snyder has suggested that this new BRT network, referred to as the “Metro Connection Tri-County Triangle,” could be built for $500 million. That price seems too low for 83 miles of exclusive busways — and it certainly would not allow for particularly ornate stations. Meanwhile, the state legislature must still approve a regional funding plan if the project’s operations costs are to be covered.

Let it be clear: Even if the BRT project provides a lot more services than the light rail for a similar capital cost, its operations costs will be far higher. Under the existing legislation, in which the federal government is prohibited from providing operations support for transit services, the only way this project will get off the ground is if the suburban counties agree to massive increase in transit funding. That may seem like an unrealistic prospect, but it is probably more feasible than assuming suburbs would agree to fund the operations costs of a city-only rail line.

None of these funding dilemmas have prevented private and non-profit supporters of the rail project, who had collectively submitted $100 million for the line, from complaining about the needs of the downtown. They suggest that a 3.2-mile line, costing $225 million and running from the river to New Center, could be funded with federal New Starts funding. Yet the U.S. DOT seems to have made clear that there will be no dollars for light rail in Detroit.

Meanwhile, Mayor Bing, unfortunately, continues to use fantastical rhetoric when it comes to promoting the BRT system: “With Detroit’s rich history of innovation,” he wrote in the Free Press, “There is no doubt we can build a system that competes with other successful BRT lines in Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Los Angeles.” Yet the development of the BRT plan should have little to do with competition; its primarily purpose must be to serve the transit-dependent population of the city. Will it get the chance to do so, or relegated to the dustbin like most other transit plans for Detroit?

¿Comments? ¿Opinions? ¿Similar News? Send them to us!